On BlueSky, there’s a bot account that uses the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s API to auto-post objects from the Costume Institute collection that are listed as open access. (There are quite a few of these accounts, for different Met departments as well as for other museums.) I like to check in on it every so often and pull out posts with particularly pretty garments, the work of specific designers, or basically any pieces I feel like I can say something about — writing a mini exhibition label, essentially — and reskeet them, adding alt text to the image while I do so.

Recently, I shared a lovely bluish-grey bustle gown from the House of Worth that had a formal day bodice as well as a full evening bodice.

So, of course, I said my little say about how sometimes women had gowns made with two bodices for different times of day, which is sort of nineteenth century fashion 101. Then something niggled at me, and I added a note wondering about the place of this kind of economy in the period. Was it a method of saving money that was broadly accepted, so that a wealthy woman might wear the day bodice in the afternoon of a weekend party and then change for the evening one for dinner? Or was it something to be concealed, for the most part, with attempts made to wear one bodice around one group of people and the other with a different group? Or, a third option, was that perhaps it was something to be celebrated — look, not only can I afford a nice gown, but I can get an extra bodice for it as well.

To be clear — I know that what everyone says is that the point was to take one skirt from day to night. But there are a lot of “everyone says”es in fashion history with very unclear provenance, and I tend to take them with a grain of salt until I explore where they might have come from and what truth value they hold. Maybe they are genuine anecdotes passed down through the generations; maybe they’re assumptions based on more recent history or what just feels right.

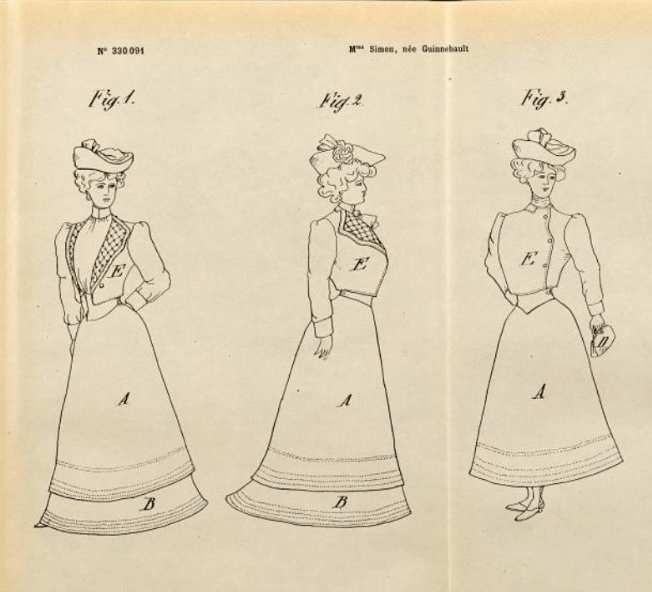

So let’s start with the name. The term “robe à transformation” is used frequently for these, and that is a historical one. However, the earliest use I’ve found of it is from 1903, and that use is not quite what we use it for today. It’s from a patent application by Mme Simon, the professional name of Marie Guinnebault (translation below mine):

Ladies are frequently annoyed in bad weather to be obliged to hold up their gowns to avoid sweeping mud from the sidewalk; if their arms are full, as is the case when they are shopping, the gown is exposed to dirt and deterioration. Otherwise, the exigencies of fashion drive women to have different costumes for when they are visiting, promenading, or traveling, which causes gross expenses. I had the idea to remedy these inconveniences in creating a transformation gown [robe à transformation] able to serve equally well as an indoors outfit or as an outdoors one, and presents also the advantage of responding to the principles of hygiene in that it no longer sweeps the ground and therefore does not pick up microbes when it is transformed into a walking dress, which will be understood by examining the design attached which presents my costume from several views.

Figures 1 and 2 show the outfit as a city or visiting dress, while 3 shows the version appropriate for walking, traveling, or sport. The skirt (A) has a flounce (B) attached with snaps inside, which could be removed to shorten it up to what’s often called a “round walking length” in English periodicals.

Other early twentieth century usages I’ve found include evening gowns with lower skirts that can be turned into capes in 1929, and references to the eighteenth century gowns that were worn rétroussée by being pulled up on cords. So I think it’s fair to say that the intent of the term was to describe a garment that could be drastically transformed in a moment, and I’m not convinced that women thought of gowns made with two bodices in that way.

It’s not bad to make use of an anachronistic term that encapsulates what you need to describe, and sometimes it’s necessary, but I do think it’s important to note when we’re doing that.

So, how did they talk about these in the nineteenth century?

I may(?) have found the earliest discussion of this phenomenon in Le Journal des jeunes personnes in 1834.

Pour robes de soirées, brodez au crochet, sur de l’organdi clair, une mouche plate, large comme une petite pièce de cinq sous, alternativement rose et noire, bleu et noir, bleu et marron, lilas et vert, rouge et vert, des nuances que vous préférez, et vous ferez cette robe avec deux corsages que vous pouvez porter selon l’occasion; l’un montant froncé, à manches longues et larges, l’autre en demi-vierge, avec une mantille de tulle brodé et des manches courtes à doubles bouillons; vous pouvez placer dans les bouillons et sur la mantille des anneaux de petites faveurs en satin de la couleur des mouches que vous aurez brodées.

For evening gowns, tambour on the clear organdie flat spots as wide as a little five-sous piece, alternating between pink and black, blue and black, blue and brown, lilac and green, red and green, the colors you prefer, and make this gown with two bodices that you can wear according to the occasion; the one with a higher, gathered neckline, with long and wide sleeves, the other with a medium-high and wide neckline, with a wide neckline flounce of embroidered tulle and short sleeves in two puffs; you can place in the puffs and on the flounce small ribbon rings in satin matching the spots you have embroidered.

(Underlining mine.) This early reference seems to treat the ensemble as, well, two bodices that share a skirt: pick which bodice you need for the occasion. I think that in this context, both bodices are for the evening, but one is more suitable for, say, a ball, while the other is more suitable for a dinner, a card party, etc.

In Fashioning Spaces: Mode and Modernity in Late-Nineteenth-Century Paris, Heidi Brevik-Zender traces a later discussion of this kind of clothing in the fashion press to an issue of Le Conseiller des dames et demoiselles in 1854. Tragically, I cannot find the article myself (this just isn’t one of the years that’s been scanned and put on Google Books or any other archive site, as far as I can tell), so I’ve only got the quotes in the book to go on.

Brevik-Zender says that the writers calls them “dresses with interchangeable bodices”, says that the bodices could be changed “in two minutes”, and claims that “a complete transformation of an outfit” could be made through changing them, pointing more toward the idea of going from day to night.

I did find a reference to the practice in Magasin des demoiselles in the same year, which does imply that there may have really been a particular trend occurring at the time:

Par économie de bagages, et peut-être aussi par économie d’argent, quelques femmes raisonnables font faire leur robe à deux corsages, l’un montant pour les visites et l’autre décolleté pour le soir. Presque toutes les robes ont des manches bouillonnées, terminées par un volant, je crois que la manche pagode sera détrônée très prochainement.

For economy in packing, and maybe also to save money, some reasonable women are making their gown with two bodices, one high-necked for visiting and the other low-necked for the evening. Nearly all the gowns have puffed sleeves ending in a ruffle, and I believe that the pagoda sleeve will be soon dethroned.

I’m intrigued by the acknowledgement of this being economical in money and space. However, this reference is slipped into paragraphs describing the latest fads (the second sentence is simply another new fashion, which I added in here because the speculation accompanying it is completely incorrect), which also implies that women practicing this economy might want it to be noticed. However again, how does that stack up against later years, when it was no longer au courant?

In the following decades, there seem to be relatively few direct references to this practice/these gowns, even though extant examples show that they continued despite no longer being novel. One 1873 reference actually is from a French/English phrasebook, which shows just how normal the concept was! The verbiage is almost standardized, as the concept no longer needed to be explained each time:

Two waists, one high and the other low, are usually made to such dresses.

(Godey’s Lady’s Book, February 1879)

An article on “Economy in Dress” in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in 1882 helps to explain the nuanced position of this practice in the American woman’s wardrobe. It claims that Americans are ashamed of practicing economy (in contrast to the French, who know that you can be thrifty and respectable), and suggests a number of elegant economies women can make, such as using sturdy Valenciennes lace and having a timeless signature gown. It also addresses how to make your wardrobe appear larger than it is:

A woman who has but one best gown can “wear it with a difference,” like the rue Ophelia offers to her brother, so as to make it suitable to many occasions, especially if she have two waists, or bodies, as the English call them. One skirt will easily outlast two waists, and therefore this is a real saving. But suppose that there be but one waist, or the dress be made all in one piece (than which there is no prettier fashion) and it should be worn one day high in the neck, with collar and cuffs on, another day with the neck turned in, and a lace or muslin fichu, gracefully adjusted with bows or flowers, and a bit of lace at the wrists, a pair of long gloves, and a more elaborate dressing of the hair, it will be scarcely recognizable. But the dress must be of a very general character, like black silk or some dark color, or the pleasure of the new impression is lost.

The implication here is that an American woman would not want the economy of a second bodice to be noticed, a change from earlier neutral references. Intriguingly, the New Peterson’s Magazine refers to having two waists as a “new style” in the same year. However, this becomes less surprising when one remembers that the years closely around 1880 were a period in which gowns were more frequently made all in one piece (as described in the Harper’s article), meaning that bodices were less likely to be able to be swapped out on a regular basis.

After this, references to gowns having a pair of high/low waists become more common than they used to be. Parisian modistes show them; Godey’s specifically calls them a “French fashion” (which makes sense, as there are a lot of neutral references to them in French fashion magazines). Table Talk describes them as convenient, and The Puritan explains that a clever woman can change up the trimmings so that nobody realizes it’s the same gown.

Unfortunately, my question remains partly unanswered. Would a well-dressed woman go from day to night with the same skirt and different bodices? Likely not in the 1880s or 1890s, at least if she were American. But anytime else? In France or England?

I’m glad, though, that at least I’ve managed to drag out some more context for the phenomenon, and satisfied myself as to the period terms to describe it.

I loved reading this! Just the kind of rabbit hole to sink my teeth into. Isn’t it interesting how people tend to use terms that were the later incarnation?

I do tend to think they did take things from “day to evening”, although I wonder sometimes if it’s because they purchased the expensive gown plus extra fabric. Perhaps things could start as one kind of gown, and a year later they add a different bodice, if they don’t do it exactly at the same time. I’ve certainly seen gowns which were made over with expensive fabric and the two bodices are of different decades, but when things are so close, like the museum example, it would be interesting to know if they were made at the same time, or if they were made just a span of time apart. Especially for high fashion, since we can easily assume middle classes would embrace the day-to-night with more enthusiasm than those who could easily afford entirely new ensembles.

Great research, as always! Loved this post so much!

LikeLike