I really do try to not be a boring pedant. (I fancy that I’m an interesting pedant instead.) I try not to be a fuddy-duddy. I liked Dickinson! And here, I loved Anna Chancellor and Rob Brydon, and a lot of the inaccurate costumes! But despite going in with high hopes for an anachronistic, post-modern romp, I was sadly disappointed for a few reasons.

I will say that part of the issue is just that My Lady Jane has to compete with Lady Jane (1986), the Jane Grey movie starring a very young Helena Bonham Carter and a very young Cary Elwes. The two stories are pretty similar despite the newer series being fantasy — Jane is admirable and clever, she doesn’t get on with Guildford Dudley until she falls in love with him, they have ideals and want to heal the realm, but they’re undermined by court politics. But Lady Jane is a well done classic that I really enjoyed. My Lady Jane … not so much.

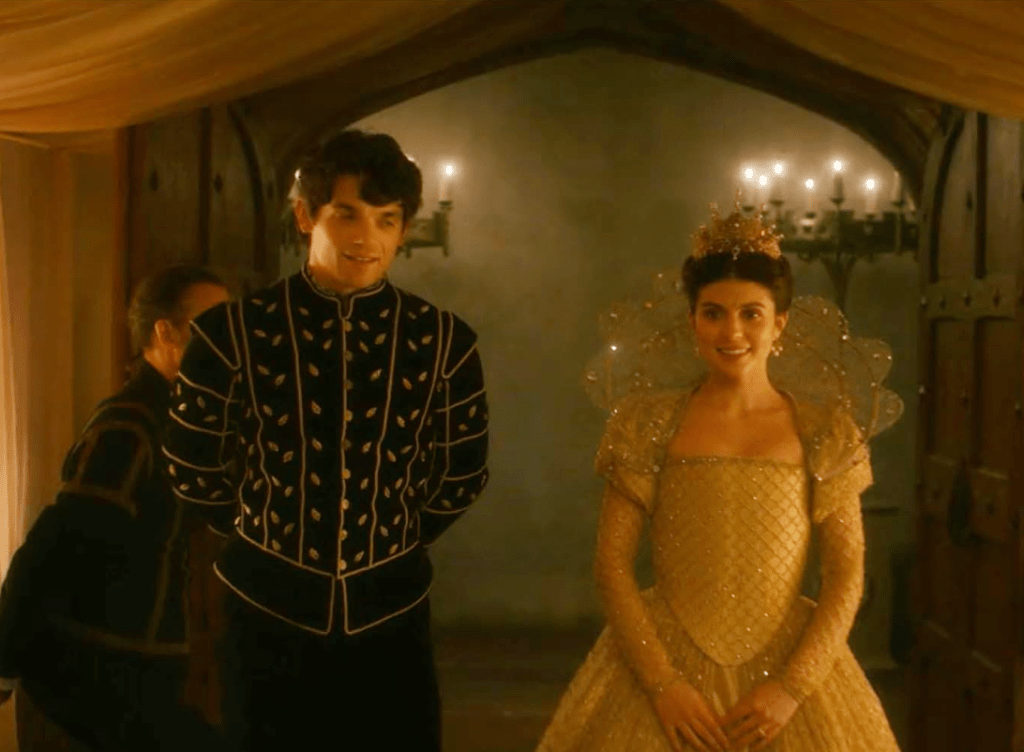

You can sum up the plotline of My Lady Jane pretty quickly. In an alternate Tudor England where there is no religious strife but instead a conflict between the dominant human Verities and the oppressed minority of shape-shifting Ethians, Lady Jane Grey is a fierce and capable modern woman. She’s forced to marry Guildford Dudley and then discovers that he turns into a horse during daylight hours. Princess Mary has been poisoning King Edward, and when he disappears, Jane is named queen. She and Guildford have to solve the mystery of what happened to Edward and try to cure Guildford’s Ethianism while Mary seeks to dethrone her. In the end, she and Guildford escape execution by running away together.

Before I really get going, I want to dig a little bit into the historiography of the Tudor period (which I’ve touched on before), because it colors everything in fiction about that era.

The story of the Tudors has been given very strong moral dimensions for a long time. England(/Great Britain/the United Kingdom) was a Protestant country by the end of it, and the Protestant/Catholic divide essentially defines those dimensions: Tudor Protestants are good, and Tudor Catholics are bad. Before the more feminist takes on him from the late twentieth century forward, Henry VIII was seen as a reasonably positive figure for ushering in the Reformation; Edward VI (a Protestant zealot) was a good young man who died too soon, Mary I was a wicked and unworthy queen, and Elizabeth I, at the helm during a “golden age” that saw the end of a real Catholic force in the country, was a paragon. And Jane Grey, of course, a learned young Protestant who was executed on Mary’s orders, was a martyr.

Mary and Elizabeth then get distorted further through the wonderful angle of sexism that loves to set up women into Good/Bad pairs. In a way, they’re perfect for it, as they’re such opposites that they invite unflattering comparisons. Mary was “old” by the time of Edward’s reign, while Elizabeth was young. Mary had a husband who didn’t love her, while Elizabeth was married to her country. Mary only reigned for a few years before her death, while Elizabeth had decades. Mary came to the throne by leading an armed rebellion, while Elizabeth simply waited to be the last heir standing.

Mary is generally portrayed as unattractive, bad-tempered, deluded, and ambitious in a very negative sense. Elizabeth, on the other hand, is portrayed as attractive, clever and learned, sensible, and a good ruler. It’s vanishingly unlikely to see any other characterizations, except perhaps in fiction set at the end of the Elizabethan era, when the queen is no longer attractive. Still, though, despite the temper she inherited from her father an the mistakes she made in her reign, she’s usually written as essentially perfect and with no hint of a resemblance to Mary.

We’ll come back to this.

The “why did they make it less interesting?” issues

A lot of the time, inaccuracies and anachronisms in historical fiction — especially when it’s aimed at The Youths — are justified as simplifying situations that are just too complicated. And there’s a value in that! Too many characters with too many motivations are going to be confusing, especially when you add in the late medieval tendency to use roughly five female names and three male names.

Another justification often given is that writers are spicing it up to make it more interesting, and I think there you run into trouble, because the judgement of what’s more interesting is so subjective. In trying to do this, I think writers sometimes end up making situations more cliché and boring. History is frequently weird and dramatic all on its own.

A big one that stands out to me in My Lady Jane is the substitution of the complex religious situation of the English Reformation with the very simple “oppression of magical people” trope. On the one hand, the Reformation is pretty complex and I would never expect a light-hearted show to really get into it; characters being presented as hardcore religious are also not necessarily going to be that relateable to the secular audience, either.

On the other, “the normie majority oppresses a magical minority out of a combination of fear and dislike of difference” is a massive cliché. I’ve seen it play out so, so many times that I’d need an original take on it to be interested, and this isn’t really an original take. A little nuance is added by some Ethians being thirsty for vengeance, but this is standard for Magical Racism plots. It also doesn’t function as an analogy for the Protestant/Catholic divide, because the characters are split along different ideological lines than the people they represent were. (More on this later as well!)

Another bit of flattening that didn’t make much sense to me was the decision to kill off Jane’s father and have Jim Broadbent inherit their estate/marry Katherine (much as I appreciated the cameo). Historically, Lord Grey was right beside Frances in pushing Jane into the politically advantageous marriage, and Katherine’s first husband was younger than her. While I suspect this was done to let Frances be more of a player in her own right and have that affair with Chad (which I also appreciated), it again resulted in a big cliché: female characters disinherited and made more powerless and abused than they actually were. Perhaps I’ve just read/seen too many period pieces!

The “I don’t think they thought this through …” reasons

There are a couple of changes that were made to the history to be fun and hip that unfortunately are actually rather problematic when you dig into them.

To come back to the Verity/Ethian conflict — while it’s kind of an analogy for the sectarian troubles in Tudor England, it’s also kind of an analogy for class conflict, and perhaps more than either, it’s an analogy for queerness. Ethians can pop up in any family and have to either leave or hide their true natures to stay safe. Ethian-phobia has nothing to do with their actions, but is strictly on the basis of them being abominations. There are Ethian bars.

And that’s fine, in and of itself! Love a good analogy for queerness. But. This show is relentlessly heterosexual. There is one (1) queer relationship, between Edward and an Ethian who helps him, and it’s very minor and is acknowledged in one “sweet cheeks” and one kiss. At the same time, men and women have sex and express lust for each other all of the time onscreen. It just does not sit well with me for actual queer relationships to be so minor while the analogy allows straight characters to wear the mask of queer transgression, if that makes sense.

This ties into the other thing that bothers me, which is the confused sexual/gender politics of the story.

My Lady Jane is definitely supposed to be feminist. It directly comments on women’s oppression through Jane and her sisters and their complaints about their situation, and indirectly makes continuous points about women’s capabilities and competence by showing female characters, particularly Jane, with tons of skills and often being cleverer than the men around them. They really are *sigh* #girlbosses. It’s a lot like Enola Holmes.

But so much about the way Mary Tudor is portrayed in the show is sexist. It’s a huge, huge mess. Because it doesn’t matter how many girlbosses you include, how many scenes where the heroine fights better than her love interest, how much random medical information she can pull out of her pocket to save the day — some negative tropes are just gendered, some deliberate changes to history seem pointed.

So, for instance, Jane is shown to be frank about sexuality (she’s introduced giving gynological care to a maid) but has no interest in sex until she meets Guilford, and even then they don’t have sex until after they’re married and after they’ve really come together. (Elizabeth shows no signs of having a sexuality at all.) Meanwhile, Mary is engaged in a feelings-free, kinky sexual relationship with Lord Seymour in which they both look grotesque, but she comes off much worse, perhaps because he seems genuinely into it while she is playacting and stringing him along for her own political needs. Jane and Elizabeth, it also has to be said, are dolled up to look beautiful, while Mary is made to look very plain.

Jane is also portrayed as totally innocent when it comes to becoming queen: she doesn’t want it, she never asked for it, she only has the crown as the result of Guilford’s father’s machinations to get his son on the throne. Eventually she becomes overjoyed with her potential to help the Ethians, and tries to work some diplomacy between the factions. (Elizabeth’s claim to the throne is pretty much ignored; she has no desire to be queen either.) On the other hand, Mary desperately wants the crown and is willing to do anything to get it, including murdering her younger brother. She believes she’s owed it, and she wants to use it to kill all the Ethians, continuing “Daddy’s” work (because she has no interests of her own).

In and of themselves, these are sexist tropes. But they take on an especially fraught angle when compared to history, because they’re all very deliberate alterations from what the writers must have found when they did any of the basic background research necessary to write the story.

The real Mary Tudor was separated from her mother as a teenager, and declared illegitimate and thus of no importance whatsoever. She had previously been considered the heir presumptive to the English throne, and suddenly had no position, dependent on whatever her father felt like giving her. Because she wouldn’t renounce her mother’s religion when he demanded it, or agree that she was illegitimate, he didn’t feel like giving her very much and would not arrange her marriage. (Henry VIII hated being disobeyed.) He would go on to marry several women roughly her own age, and she watched as he abandoned her younger sister in much the same way he’d abandoned her, executed Kathryn Howard, and died. Throughout his reign and that of Edward VI, she was in danger of being imprisoned or killed herself due to her Catholicism. People rejoiced when she overturned Jane Grey, because the country was still pretty Catholic and felt she was a more legitimate monarch than her cousin (which is how she raised so many troops); she also showed no interest in executing Jane and Guilford until Wyatt’s Rebellion, a Protestant uprising that directly threatened her. She at last achieved her royal marriage, but her husband was both piqued at marrying an older bride and at being an equal or subordinate partner to her, and instead of having any children she suffered from medical issues that have gone down in history as the result of delusion and her unsuccessful marriage.

Did she do/allow bad things? Of course, but blood soaked the hands of all the Tudors, who were never really safe on their throne due to the fact that they stole it in the first place. They constantly faced rebellions and had dozens put to death each time.

So in characterizing Mary the way the show (and I’m guessing the book) does, it’s not just making up a character who fits into multiple negative female stereotypes, but twisting an actual person who was much more complex into a sexist caricature.

There are good points to My Lady Jane, parts where it’s fine and even enjoyable! But I think Lady Jane managed to do a better job of turning history into an emotional love story with a tenuous connection to the truth, largely because it avoided all of these potholes.

Having read that book on Elizabeth, I can actually follow along with the analysis here! I won’t watch the show, but maybe would Lady Jane. Who was the subject of a Rolling Stones song, BTW.

LikeLike